論説

概要

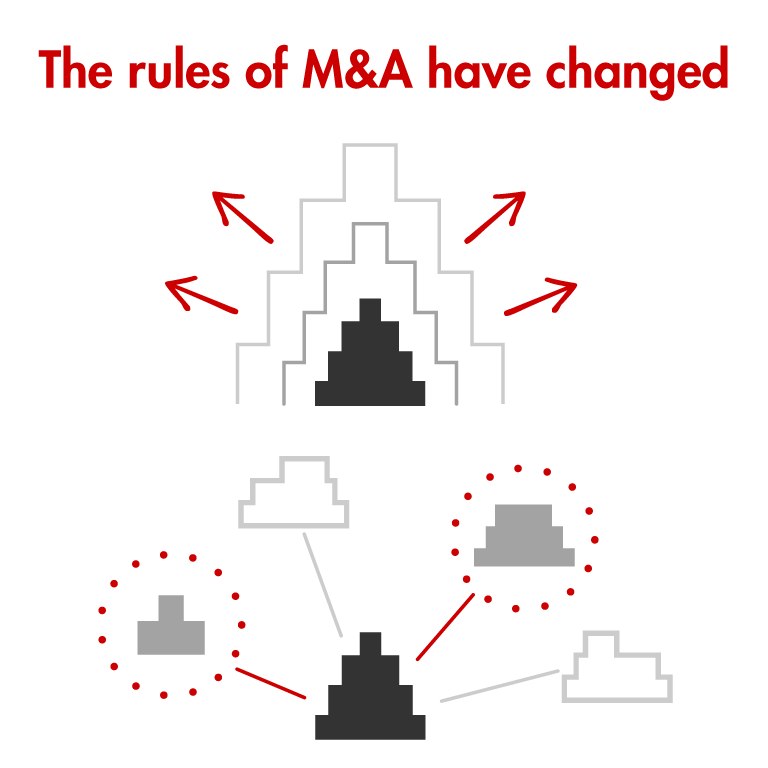

- Over the past few years, industry disruption and growth challenges have changed the rules of the game for consumer products companies.

- In addition to initiatives to spur organic growth, many are turning to M&A, especially scope M&A, to respond to these challenges.

- At the same time, the industry continues to attract attention from financial investors and activists.

- To be successful in this new environment, the best consumer goods companies frequently update their M&A playbooks across strategy, diligence and integration approaches.

For decades, consumer products companies typically joined forces in megamergers designed to build scale and market-leading positions. A wave of consolidation has swept over the industry in the past 10 years, including some of the largest deals inked—Anheuser-Busch InBev and SABMiller, Coca-Cola bottlers’ integrations in Europe and Japan, and Mars and Wrigley, among many others. This was a tried and tested formula to boost earnings growth and margins, as well as the next round of consolidation.

The changing rules of the game

Now, companies are finding that’s not enough to help them respond to industry disruption. Times have changed. Nimble insurgents are taking an outsize share of category growth, Bain & Company research finds. While they may account for only 2%–3% of market share for the categories where they are present, they captured over 30% of the growth in those categories over the last four years, up from 25% between 2012 and 2016. (For more, see “How Insurgent Brands Are Rewriting the Growth Playbook” and Local Insurgents Shake Up China’s “Two-Speed” Market.) Incumbents also grapple with digitalization, the emergence of low-cost retailers and online/offline retail ecosystems, and an unavoidable new fact of life: The benefits of scale in everything from media buying to retailer negotiations to go-to-market strategy are diminishing.

These factors, combined with an internal focus on the bottom line, have led to a growth slowdown for most consumer goods companies. In response, firms are taking short-term actions, such as trading off margins to regain market share. They are also undertaking different types of deals.

Updating the M&A Playbook in Consumer Products

As scope deals surpass scale deals, the old rules for acquirers no longer apply.

Responding to industry challenges with scope M&A

Strategic deal value in the consumer products industry increased by 9% to reach $181 billion in 2018. In addition to engaging in more M&A, many CP executives are turning to scope deals. Bain’s analysis of the top 200 strategic deals in consumer goods from 2015 to 2018 shows this rise. For the third year in a row, scope deals outnumbered scale deals (see Figure 1). Scope deals are intended to spur growth in fast-growing new markets or geographies, or to get access to critical capabilities—not only to increase scale or generate cost synergies. Scope deals like the Keurig Green Mountain merger with Dr Pepper Snapple and Coca-Cola’s purchase of Costa Coffee now represent 66% of consumer goods M&A.

As these acquirers are learning, scope deals are harder to get right. They are more expensive due to higher deal multiples, which reflect the superior growth profile of the target assets. They call for new approaches to diligence and integration. They often require a new operating model to allow people to work together. Yet, they are increasingly an antidote to stave off the pressure of disruption while addressing the growth imperative.

Ongoing involvement from financial investors and activists

At the same time, financial sponsors, mainly private equity firms, are evolving their role. Many sponsors are behaving like strategics, with long-hold funds of up to 15 years, megafunds that enable megadeals and add-on dealmaking that drives industry consolidation. Add-on entries made up around one-third of all sponsor deals a decade ago. They comprise close to half of the total today.

While strategic acquirers still represent the overwhelming majority of deals (see Figure 2), financial sponsors like 3G Capital are increasing the competition. The number of private equity buyout firms hunting for deals has risen steadily each year for a decade. They are more active and hold record levels of uninvested capital. In addition to being competitors, they are also potential buyers of noncore businesses that consumer goods companies want to exit. More sponsors are proactively approaching consumer products companies with offers to buy assets that are not yet on the market.

Meanwhile, activist investors are intensifying their demands for companies to be sold in whole or in part. Between January and October 2018, across all industires activists targeted more than 800 companies. Overall, more than 20% of activist campaigns focused on M&A. This is no longer a US trend limited to the likes of Campbell Soup and Procter & Gamble. The trend has moved into Europe—think Danone and Nestlé.

This raises the bar on up-front strategic thinking for proposed deals and the preparation needed for shareholder engagement. Global consumer goods companies now need a proactive approach to managing and strengthening their portfolios, with a sharp eye to the value they add category by category. To avoid being surprised, many have learned to look at their business through an activist lens. As incumbents seek to become nimbler, with more focused category leadership, the spate of divestitures will likely continue.

To be successful in this new environment, the best consumer goods companies are updating their M&A playbooks across strategy, diligence and integration approaches. Let’s look at these areas one by one (see Figure 3).

The imperative to future-proof M&A strategy and screening

More than ever, M&A strategy is the critical starting point for acquiring the assets and capabilities to support a company’s broader growth agenda. In today’s disruptive environment, there are two imperatives: embedding future-back thinking and adopting a broad portfolio approach to dealmaking.

Meeting current growth challenges requires taking a today-forward view of the business. This means looking hard for sources of growth and cost levers in the existing business footprint. Fundamental business transformation, on the other hand, requires taking a future-back view—that is, forming a vision of what the company should look like five years from now and redefining the corporate identity along those lines. Combining these views should be the starting point for M&A strategy (see Figure 4).

M&A strategy thus moves beyond market consolidation motives to guide the assets and capabilities that the company needs to acquire to fulfill a future-back mission. We expect a continuation of more growth- and capability-focused dealmaking as the long-term strategic focus pivots to the top line. Three new types of M&A together support this portfolio approach.

- Scale insurgent acquisitions: Consumer goods companies are buying fast-growing scale insurgents to further accelerate insurgent growth, leveraging capabilities such as global distribution. That's why PepsiCo acquired sparkling probiotic drink maker KeVita, for example.

- Cross-sector acquisitions: Incumbents also are pursuing cross-sector acquisitions to move up the value chain to higher-margin, fast-growing, service-oriented offerings. In a world where the lines between products and services are blurring, these deals are expanding traditional business boundaries.

- Corporate venture capital (CVC) investments: Meanwhile, established consumer products companies are making CVC investments in emerging brands and business models. The amount of corporate venture capital invested in consumer products increased sixfold from 2013 to 2018. These companies recognize that CVC investing will allow them to move fast enough (or identify the trends early enough) to capitalize on new opportunities. For example, Diageo’s Distill Ventures enables it to make small bets on emerging brands as consumer preferences change to healthier alternatives within the alcohol market.

Bain Partner Allison Snider explains how brands can get ahead in a changing landscape with deals that broaden the scope of their offerings.

Redefining due diligence

When pursuing scope deals or insurgent brands, companies need to be able to articulate why they are the right parent. What are the incremental and scalable capabilities that can accelerate the target’s growth trajectory? Articulating the synergistic value is also a point of differentiation from private equity players that may be looking at the same assets.

The focus of diligence is on the future market potential. Fast-growing assets, especially early-stage ones, are particularly tricky to evaluate for potential profitability at scale, yet the ability to be profitable at scale is a key input into the deal model to justify the valuation. We outline a simplified framework that many leading acquirers use to assess the future growth and profitability potential of insurgent brands (see Figure 5). This structured way to evaluate brand fundamentals helps acquirers increase confidence and clarity about how brand penetration may evolve and how they can use their own infrastructure and capabilities to accelerate it.

Given that scope acquisitions typically command 30% higher valuations and generate about 30% lower cost synergies than scale acquisitions, the acquirer needs to be comfortable with some uncertainty: No matter how robust the diligence, the deal may not deliver the expected value. While the potential growth rewards may be tremendous, so are the risks.

Overcoming integration risks

Consumer goods companies face unique risks when integrating scope deals or insurgent brands—for example, paying too much up front, scaling them too quickly, burdening them with business processes and planning, and losing critical talent. Taking the wrong approach initially makes it more difficult to course correct later. The integration setup needs to ensure that the acquirer doesn’t crush the acquired asset under its existing weight, killing the very culture that led to the acquired brand’s growth. Often, the answer is a physical separation of headquarters and personnel to protect the brand’s culture and ways of working.

The flip side of overintegrating—keeping the brands entirely separate from the base business—doesn’t help to meet growth objectives, either. The acquirer can end up with a portfolio of assets that do not benefit from shared learnings or from the acquirer’s infrastructure. Successful integration relies on the deal thesis to dictate the integration thesis, which defines what activities should be integrated vs. kept separate. Companies need to ensure that the founder or founding team has the independence to make the most strategic decisions in areas such as product development, specialized sourcing and branding.

The functional integration approach in such deals requires an assessment of where to combine to gain scale efficiencies, where to keep the functions separate and where to invest to strengthen core capabilities. Integration approaches can allow the acquired company to opt in to any proposed functional integration. For instance, when L’Oréal bought makeup brand Urban Decay, it kept product design and R&D separate to protect the target’s creative independence and maintain continuity for customers. On the other hand, procurement in select categories and production were combined where possible to reduce costs through scale efficiency. Also, sales and distribution were integrated to expand Urban Decay’s international footprint utilizing L’Oréal’s distribution reach.

The best consumer goods companies not only update their M&A playbooks along these lines but they also acquire frequently. A repeatable M&A model that includes frequent activity is a proven contributor to success. In fact, our M&A value-creation study, spanning 2007 to 2017, shows that frequent acquirers (those that completed 10 or more deals over that period) outperformed infrequent acquirers by 35% in terms of total shareholder return.

In the face of disruption and growth challenges, many consumer products executives are looking to scope M&A. This profound shift will change how they think about all areas of the M&A cycle, from strategy through diligence to integration and ongoing management. However, as the early experience of some companies shows, clarifying the strategy and mission, developing a portfolio of bets, and adopting a fit-for-purpose diligence and integration approach will determine the winners of the future.

Peter Horsley is a Bain & Company partner based in London, and Allison Snider is a partner based in New York. Both are members of Bain’s Consumer Products and Mergers & Acquisitions practices. Brian McRoskey is a partner in Boston and a member of Bain’s Consumer Products and Organization practices. The authors would like the thank Shikha Dhar, Practice Manager in Bain’s Mergers & Acquisitions practice, and Charlotte Apps, Practice Director in Bain’s Consumer Products and Retail practice, for their contributions to this work.

How Insurgent Brands Are Rewriting the Growth Playbook

These small brands now capture more than their share of the growth—and no category is immune.

Local Insurgents Shake Up China’s “Two-Speed” Market

Incumbents can compete more effectively by adopting critical ingredients of insurgents’ success.